|

Ji-Hoon Byun, Duk-e-um |

The multiple effect within the sedate walls of the Art Museum is of disruption–conceptual and perceptual –invoking Paul Virilio’s museum of accidents, the necessary adjunct to every edifice celebrating technology’s ‘progress.’

"A young woman appears behind a perfectly stacked table contemplating a pile of objects" begins the scenario for Heman Chong and Corrina Kniffki’s video work Divided Tonight (2003). "Give it up now. Don’t think. No more thoughts. Give in tonight." Suddenly in one simple action she collapses the whole shebang ("everything she has used in the past year") and down it comes in one almighty crash that resounds through the gallery. "Everything explodes. Tabula Rasa sans irony." The camera moves in on the subtly smiling face of the perpetrator. The closer it moves, the wider the screen, until the blurred face of the woman is yet another distant memory, her white collar and jacket holding out longest, before everything empties into white. And then, inevitably, in the way of loops, the image is back in our faces with its evidence of conspicuous consumption to be destroyed for us again and again in this small but satisfying act of wish fulfilment.

Next door, Feng Mengbo has set himself the grim narrative task of recording The last three minutes of the earth, a haunting effigy with detritus in close-up and a lone bug documented in grainy, scratched, black and white 16mm film which says something about built-in obsolescence and the new technologies.

Round every corner, through every white-curtained doorway are more hints of the precarious calm of the times in a range of evocative titles. In The 21st Century’s Big Big Sci-Fi Disaster Horror Movie, an indolent group of Japanese workers and apartment dwellers gathers for an earthquake simulation exercise which you hope for their sake, never happens (then, days later it does!). In Baghdad in no particular order, 66 pictures before the fall, a small boy blinks in a room full of casual chatter. An alarm from the work next door invades the temporary calm. In Nothing happens: 8 normal Saturdays in Linz only the viewer’s perception of an otherwise uneventful street scene on the screen is alerted by the sound.

I’m reminded of sound artist Bruce Mowson’s comment at a MAAP artists’ talk at Nanyang University yesterday describing the drawbacks of creating sound works for public places–"only to be attempted if you’re feeling crazy." He designed a work which included the sounds of buildings being destroyed but found that only the sound of dogs barking and babies crying attracted attention–"which makes sense" he said. Mowson has installed a more subtly insistent work in the Gravities of Sound exhibition in the Tunnel Underpass from City Hall MRT entitled The End of the Tunnel Is Now Approaching, which are just some of the words heard in transit.

Encouragingly, there’s a strong emphasis in the SENI exhibition on political activism and a resurgence of collective responses to the world’s inequities in the work of groups such as Fondation Arabe (Lebanon); 16 Beaver Group (USA) for whose members, many of whom originate from West Asia, "the security obsessed post-9/11 realities in the US have highlighted or brought into question public rights, and in particular the diminishing space for alternative viewpoints"; The Artists' Village (Singapore); Spacecraft (Malaysia); Big Sky Mind (Philippines); Taring Padi (Indonesia); Project 304 (Thailand) and sciSKEW (Singapore). And there’s plenty of playful experiments and dancing among the ruins.

Elsewhere in the Singapore Art Museum and on our way to MAAP’s GRAVITY show, we come upon the work of Tan Swie Hian, one of Singapore’s most celebrated artists. One of his small illustrated fables, entitled Time, prepares our way.

The green moss silently asked the rain water that was draining away if it remembered its form, sound and feeling when, a moment before, it was falling onto the moss-grown ground. 8 Fables by Tan Swie Hian

MAAP in Singapore–GRAVITY

Circuit boards, keyboards, cables take on a life of their own in Xing Danwen’s disCONNECTION. Neatly sorted and seemingly colour coded, technology’s refuse re-assembles itself for its next life. This is pollution, though of a strange new order.

Throughout 2002-3, Xing Danwen documented the huge amounts of ‘e-trash’ shipped from industrialised countries like Japan, Korea and mostly the US and dumped in South China’s Guangdong Province where workers make their living recycling it. A potent "visual representation of 21st century modernity" if ever there was one.

|

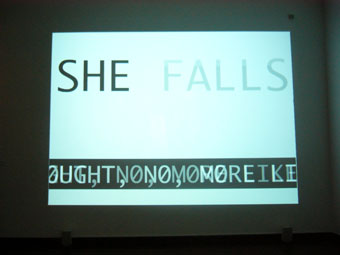

Young-Hae-Chang Heavy Industries, All Fall Down |

Audio voices and video texts (reproduced word for word at the same time) uncannily collide in Grant Stevens’ Dazed and Praised in which the subject (for those like me who don’t read the catalogue till later) is disappeared and any number of possibilities present themselves (as we now know from Bill Clinton, it depends on what you mean by ‘it’) while you simultaneously read and listen to voices and background music reminiscing about the thrill of action, of change and revolutions in popular culture: "We loved doing it. I’m doing it. I can do it!"

Marcus Lyall’s volunteers in Slow Service await the ‘accident’ with the same tremulous nonchalance of Heman Chong’s willing subject in Divided Tonight as a selection of foodstuffs are hurled at their heads. Here, there’s sharp definition in the place of blur but time passes as strangely and evocatively in sumptuous slow-mo splashes of liquid flight.

Merry hell is on offer in Teck Tan Wang’s magical little box of tricks, Pan Opticon, in which you shake a small box and violently rearrange the digital furniture right around the room as you see fit. Shu Lea Cheang’s transgressive web work, Burn takes copyright violation to one logical conclusion, providing a stack of CDs for visitors to play pirate and DIY their own compilation disc from grabs of music which they select by colour (Pink?) and word (Cake?) to take home with them.

Kim Kichul whose background is in sculpture and who sees sound as "structural material which is just not visible" offers a playful if confronting aural experience in Sound Drawing in which the visitor draws a graphite stick across a piece of paper and the movement, the drawing, transforms into the lines, loops and squiggles of raw, squealing and grating accidents sound. (See Gail Priest’s article on Kim Kichul, "An eye for sound"). In contrast, Kim’s work for the Gravities of Sound program has sound raining down on commuters as they pass through the tunnel.

The happiest accident comes in the form of Ji-Hoon Byun’s Duk-e-um which heads up the MAAP exhibition and to which, like other works in the exhibition, I found myself returning. A digital lightfall in Yves Klein blue it mirrors the movement of water but offers pleasures all its own as you walk past or stand within its ambit and it answers the movements of your shadow with radiant sprays of white light against the blue. For a moment, you hold destiny in your hands.

GRAVITY, MAAP at Singapore Art Museum, curator Kim Machan, Oct 27-Nov 28; SENI: Singapore 2004, Art and the Contemporary, Artistic Director Chua Beng Huat, Singapore Art Museum, Oct 1-Nov 28

RealTime issue #64 Dec-Jan 2004

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to [email protected]

back

back