|

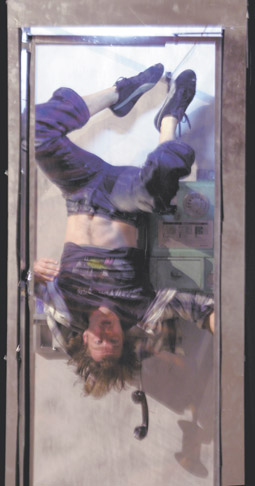

Grayson Millwood, Roadkill, Splintergroup photo Tim Bates |

Roadkill is a kind of Wolf Creek for dance, theatre and contemporary performance audiences. It's not the usual populist fare for the stage, but here is a work about fear that engenders various states of suspense. Splintergroup pull this off by first creating a palpable, realtime realism: a lone car on stage, a man and a woman in it, one asleep, the sound of early morning bird calls, a phone box. This quiet scene is returned to several times, while the horrors that happen in between (a threatening male stranger, possible collusion between the men, relationship breakdown, a storm of raining rocks, assault, death, ghostly apparitions) are soon revealed to be the fearful imaginings of the couple about what might go wrong when your car breaks down in the middle of a very white Australian no-where. But fantasy here is always rooted in the real, in the substantiality of the car, the phone box and three resilient bodies.

The challenging shift from realism to dance in Roadkill is dextrously handled. There's a teasing, rough dance from the first man on the car roof. Later, after he's crashed the car, the stranger emerges from it in a pulsing, tottering dance of shock, real but unreal. Other events are hyperreal, the woman pulled through an open car window for some hilariously impossible wild sex. Without film's advantage of calculated points of view and editing, Roadkill also has to transform literal images into abstract but evocative ones. Instead of a car smashing into a human body that will bounce off the bonnet onto the windscreen, a dancer will repeatedly throw himself at the car.

When passages of dance in Roadkill emerge they seem a naturally fantastic part of this heightened reality. The two men do an odd dance of limited contact and apparent indifference (replete with nose-picking), falling against each other, heads crashing onto shoulders, as if afraid of hand contact. As the male-female couple dance, she reaches up. He pulls her hand down, his other hand frequently around her neck. It's as if he's trying to contain her, earth her, "stop her floating away" (as one of the artists put it in the Q&A). Later he'll weight her inert body with the stones that rained down earlier, and (in a curiously necrophilic moment) drive a toy car over her, it's headlights glaring at us through the dark. Soon, she'll tread all over him—thighs, chest, buttocks—in a strenuous, halting dance of containment.

Lighting, sound and dextrous human movement are the principle means in Roadkill for duplicating film's capacity to make us fearful of what's just outside the screen frame. Seamlessly segued blackouts disappear figures in the car or phone box or re-appear them in half-light as stalkers. Luke Smiles' ingenious sound design creates sound bubbles around the characters—the men talk outside the car but as soon as the door is shut the woman and the audience hear only the car radio, the first stage of her growing paranoia. Roadkill frequently suspends our disbelief in its transformation of the real into the surreal. The stranger is revealed in the phone box, turning upside down, moving as if in liquid, the receiver floating above him, and, finally, we see only his legs, as if those of a hanged man. Roadkill's various scenarios thankfully never resolve into a single suspense narrative, although there is some sense of resolution, albeit ambiguous, for the couple.

So, what about the relation between dance and suspense? There are those moments in ballet where an almost inhuman figuring is achieved and held (like the opera tenor's high C). We await these moments of suspension in a state of suspense. Can the artist pull it off? We admire a dancer's capacity to take flight. The documentary evidence of the dancer's brief but high suspension in space is revealed almost immediately in the projections of Lois Greenfield's onstage photography in the Garry Stewart-ADT Held. This freezing or suspending of time has to be seen in the context of modern dance's engagement with physical theatre, break dancing, martial arts and other codes, where tension is heightened by a sense of disbelief at the speed and risk involved in performance. And it's rarely about narrative. Of course, ballet has its narratives and, although we know the stories, we tense up as the critical point nears, hoping that an artist of genius can replicate for us again the feelings of not just empathy but a physical correspondence and some kind of transcendence.

Conventional narrative suspense is at the core of Roadkill's effectiveness, but working from and commenting on horror films, Splintergroup cleverly and effectively mimic the genre without ever parodying it. They complicate it by shifting points of view and pushing into surreal territory about fear and desire, and the love-hate bonds of coupledom, most emphatically in the grim images of mutual containment. These horror film fantasies appear mere projections for a deeply troubled relationship caught in a moment of suspension between the real and nightmare.

Splintergroup, Roadkill, choreographed and performed by Gavin Webber, Grayson Millwood, Sarah-Jayne Howard, composition, sound design Luke Smiles/motion laboratories, dramaturg Andrew Ross, lighting designer Mark Howett, Bluebottle, producers Brisbane Powerhouse, Dancenorth, toured by Performing Lines for Mobile States; Arts House, Meat Market; March 5-8; Dance Massive, March 3-15

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to [email protected]

back

back